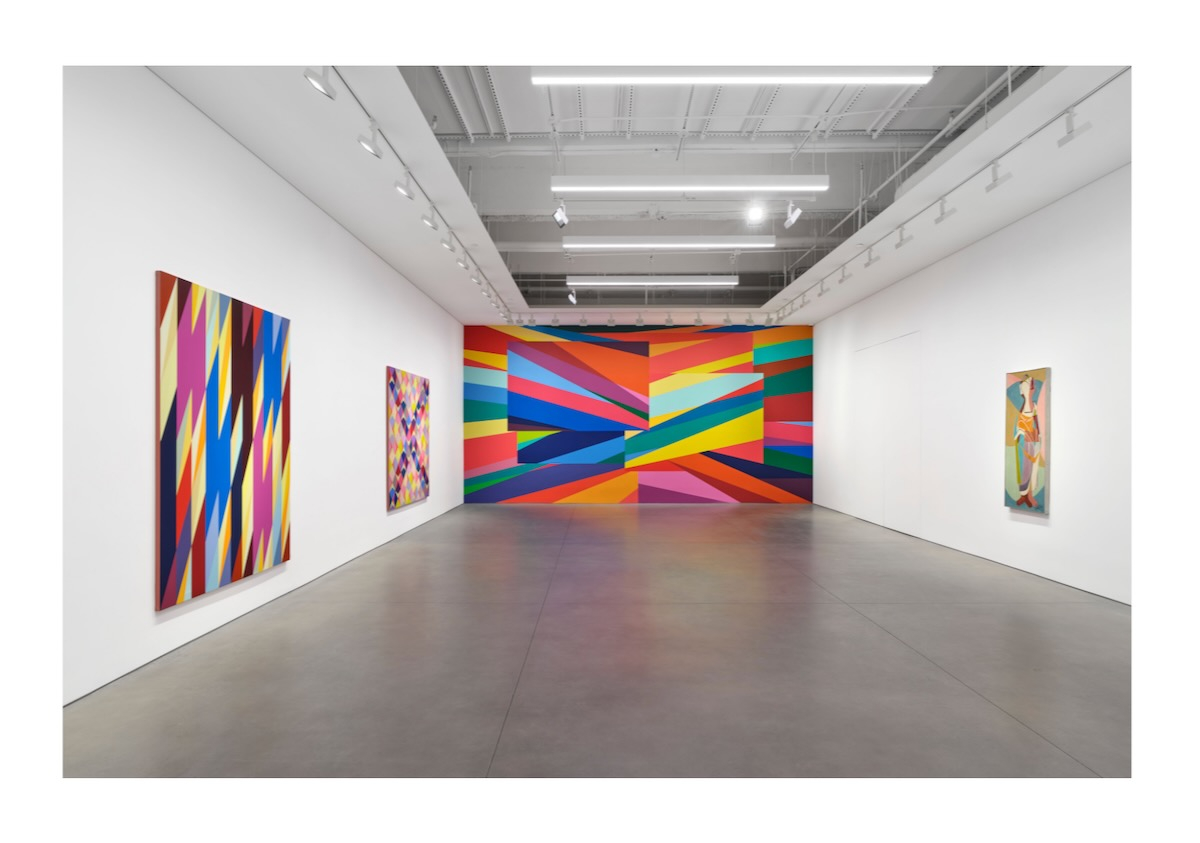

Odila Donald Odita: Shadowland

Kordansky Gallery, NYC

January 15 – February 28, 2026

"Fear is the flash, the gorgeous dress our skeleton wears." - Dambudzo Marechera.

It's better if the content of a painting is clear or at least available when you look at it. If not, you need a statement to guide the observer. Often, with abstract painting, writing the statement may require more lucubration than usual. Why these colours, why these forms as opposed to any others? It might end up being as significant an artwork as the paintings themselves.

Odili Donald Odita creates acrylic paintings and wall murals. He was born in Nigeria and raised in America. He has made the intersection of the two cultures a reason for making the work.

This is Odita's second show at Kordansky Gallery in Chelsea. He has included some paintings by his father, who was an artist in Nigeria, and some of his own identity-oriented photographic work from the '00s. The inclusions suggest that he's not sure if the work will communicate its purpose without some background information. The rest of the show is work made in 2025.

At some point in the late '90s, the influence of Illustrator, the vector graphics editing program, was felt across the visual culture. The patterns were used for digital wallpaper, desktop backgrounds, and in the physical world, sometimes as nightclub murals. They seemed to reflect the digital optimism of the era. You could hover over an area with your dropper tool and fill it with your bucket tool in any colour you fancied. Fashion designers like Diane Von Furstenberg used it to update Emilio Pucci's patterns, and some artists decided that the vector images might make good paintings. It was a large part of Franz Akkerman's work. I think I noticed it first in 2000 in a Mathew Ritchie show at Andrea Rosen Gallery.

But after a while, it faded away. There were all kinds of other ways to make images on the computer.

Once Odita had adopted the look, he took a few years to refine it and then produced a lot of quite similar-looking paintings. There are some key motifs in the work. The squashed and fractured stripe painting that might be seen as a landscape, as inHeavy 2025 or Future Perfect from 2008. The loose verticals with a diagonal cut, as in Cut 2025 or Cut 2016 (lithograph). There are the diamond-shaped patterns that appear to have a figure in the middle that could either be "Nude Descending a Staircase," or a figure (sometimes figures) dancing. Like "Protector" in this show or "Here and There" from 2008. You get the idea.

There are lots of interviews online in which the artist talks about his relationship to Nigeria and how it informs his work, yet "Protector" has twenty-eight different colours. I still can't pick out which ones are Igbo and which are American. It's not like looking at a Mary Heilman. There is a lot to choose from. Also, I don't know why a digitally derived image should be a painting rather than a print. The associations are with weaving and block printing, so is the complete lack of human touch somehow ironic? Only the slightly raised ridge along the taped edges remains.

But more than that, there is a caution at the centre of the work that I can't ignore. For example, he often uses a marigold yellow as a highlight colour, but unlike Akkerman, he can't let it stand on its own. In "Camouflage," on either side of this coloured shape, there is a sliver of yellow ochre, or in other places, it has been backgrounded by a low-key azure blue. One shape has a line of dusty mauve running through it, but despite being its colour opposite, it merely subdues it. The whole effect throughout is one of balance, of resolution. The colour arrangements have sanded down any rough edges, and the forms themselves have suffered from the heavy toll that Shutterstock vector wallpapers have demanded. It looks too much like graphic design.

"How do you observe a stone that is about to strike you?" - Dambudzo Marechera

Watching them pluck our friends and neighbours, our loved ones, out of the crowd because of the colour of their skin is the worst thing I've ever seen in my life. But anger and fear alone cannot make great art. Max Beckmann's ghastly shadows depended on his detachment, and David Hammons' blade was whetted by critical judgment.

I don't think all artists should or could be actively political; the act itself is political.

I understand that Odita came up at a time when it was harder for black artists to get gallery shows; he may have felt it was necessary to get his point across subtly. But today, I believe, if it can be said, it should be said without a filter.

Odita's statement at the gallery's front desk asks you to consider his work as a philosophical reflection and a meditation on how political forces shape what you perceive. It's a lot for this work to carry.