Those who keep up with the more avant-garde end of the jazz spectrum have long known that Matthew Shipp is one of the great pianists, but he's reached a higher level of creativity this decade, most recently displayed in his two releases this year, the new solo album I've Been to Many Places and the trio album The Root of Things.

Quick recap of how he got there: While growing up in Delaware, Shipp studied privately with Dennis Sandole, one of John Coltrane's teachers. Later, at New England Conservatory, Shipp studied with Joe Maneri, another avant-jazz great. Shipp's recording career began in 1988 with a duo album with saxophonist Rob Brown, and within a few years the pianist had joined the David S. Ware Quartet; he recorded with that group from 1990 until it disbanded in 2007, then increased his already prolific output by making over two dozen albums as leader or co-leader in less than eight years -- eleven with Ivo Perelman, his most frequent collaborator lately.

Your new album is your ninth solo album. You told me, after your first, and accidental, solo album in 1995, that you felt uncomfortable playing solo. Obviously you got over that.

Yeah. The thing about solo playing is, you can be a really good pianist, or a great pianist, but to pull solo off, you have to have a real specific concept, and I feel that I've developed one over the years. I have an approach and a technique geared towards my approach. Not technique for techniques' sake, but a technique geared towards whatever my imagination is trying to do when I play solo. So I've grown into a very specific approach for solo, and I feel very comfortable with it.

When you play solo, you often do medleys of your compositions, but not when you're doing duos or other kinds of collaborations.

I guess with duos and other things [with] a partner there, I can't be self-indulgent and go into whatever I want to because I have to take into consideration where that other person is. When I play solo I have the complete freedom to switch up any gesture or put things together that sound counter-intuitive, and try to find the sense between different gestures that might not naturally seem like they belong together. Playing solo you have the complete freedom to do that, because I don't have to worry about somebody else's vocabulary or where they're at or where they might want to go or where they might go. I kind of got this from David Ware. The material is valuable and it can lead you anywhere. Theoretically the pieces of the puzzle can fit together millions of different ways, so a solo concert is a chance to flex my muscle to see how the pieces of the puzzle can fall together different ways.

In your collaborations with Darius Jones, on both of those albums all the tracks are dually credited, and yet so often I wonder, "Is that composed?"

In your collaborations with Darius Jones, on both of those albums all the tracks are dually credited, and yet so often I wonder, "Is that composed?"

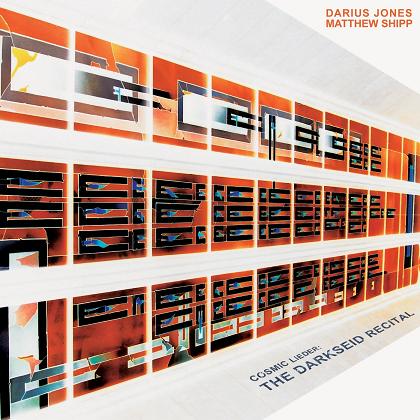

Well, we take a very composerly [approach] -- I mean, they're art songs of sorts, Cosmic Lieder [the title of their first album - ed.]. He was the one that suggested we approach this duo that way and make it different than something I'd do with Sabir [Mateen] or with Ivo [Perelman] -- even though the stuff with Ivo has that characteristic, Ivo's still a tenor player in, I don't know what you'd call it, a post-Coltrane idiom.

You recently did a duo with (Shipp Trio bassist) Michael Bisio.

We do a lot of duo concerts, and our duo album, Floating Ice. Playing duo with Mike is different than the trio, because the trio's more of a program thing, where in the duo we really just let loose and I don't try to control it like the trio, to some extent. I hate to say it, but the trio is more of a semi-commercial product in that it's a standard jazz instrumentation, we can put it into a jazz club and even though we're doing our music, we kind of present it as if it were the Oscar Peterson Trio. [laughs] Even though it's not, but the presentation is a very jazz presentation, whereas the duo is more open and free-flowing in that sense.

What's reflected in the title of your most recent trio album, Root of Things?

What's reflected in the title of your most recent trio album, Root of Things?

Well, my whole thing is always trying to get back to the essence. That's why in 1999 I named an album DNA. So I'm always trying to get back to what generates something, what creates something, why does this exist? I'm always involved in that in the music, so that's another way to explore that but say it in a different way. DNA, or Equilibrium, which deals with a psychological balance. New Orbit, which is 'things are always new and always the same.' So you can go around that theme with many different variations.

Do you do any teaching?

Yeah.

How do you approach that?

Usually people that want to study with me want what I have to offer. I basically just see where they're at and I try to find out what their practice routines are and I try to open their minds to different ways of practicing. Because they have to discover who they are, I can't. I think I have insights into how I practiced and found out who I am, and certain things I learned through that process, I might be able to help people find out who they are, so I can open their minds to some approaches to practicing and some approaches to dealing with influences and trying to both use it to learn more language but not get caught in it. And I think I have some insights into that, so I think I can be useful to people, but I have nothing doctrinaire about what I tell students. I feel I was really lucky. I bumped into my style. I had an open mind, I always wanted to have my own style, and it happened. I don't know if that was luck, predestination for that to happen, or what. But I feel, not lucky, but I feel thankful that it happened, and I feel that I understand that process of trying to find your style.

It's really interesting, I was talking to William Parker this morning – I have breakfast with him a few times a week – and we were saying, there's people that never study, and they have their thing; there's people that kind of study, and they have their thing but you don't really know how it happened – say, McCoy Tyner's like that – and then there's people that are extremely studied, like Cecil. It's kind of funny, the whole continuum exists. Somebody like Hampton Hawes never studied, somebody like an Erroll Garner. Somebody like McCoy, you know he took some lessons and stuff, but it's still a mystery, and he's not extremely studied, but you know he did do something. And then there's people like Oscar Peterson, Cecil, whoever, that extremely studied. It's interesting how we all are trying to get somewhere, but everybody has their own way of getting there, and it's all different. Everybody is so unique in who they are, how they get there.

You don't create your style, you bump into it, you uncover it; it's a discovery; it's there. But you have so many blocks getting there, you have to break down the mental blocks to get there.

It's kind of a contradiction in that you have to consciously work on things until they're not conscious anymore.

That's the learning process, even driving a car is like that. That's the whole learning process in general. I don't see that as a contradiction, I see that as, that's how you learn. You have to do things over and over until they become part instinct. I guess instinct's not the right word, because instinct usually means something that you're born with.

It's sort of a reflex.

Right.

Speaking of influences, have I pissed you off yet with my frequent references to Mal Waldron when reviewing your albums?

No! Mal is a one-of-a-kind-modernist -- there is no one quite like him in jazz history, from playing with Billie Holiday to Steve Lacy to Eric Dolphy and Jeanne Lee. He is the bridge between [Thelonious] Monk and Bud [Powell], for he understood the linear sense that Bud developed, and could employ that if he wanted, and he understood the iconoclastic stance of Monk -- he crystallized all that into dark, crunching modernism and at times minimalism within the jazz idiom. No one is like Mal. - Steve Holte