There was a furor in the classical music community over The New York Times music critic Anthony Tommasini's recent list of the ten greatest classical composers. The author himself characterized the project as "absurd." It's not that his choices were outrageous, though of course there were plenty of commentators chiming in that some of their favorites had been left off. It's that ten is an absurdly small number. One doesn't really learn anything from such a list, and as has already been suggested, some people might get the erroneous impression that in the whole long history of classical music, there haven't been all that many great composers.

Well, I love making lists, and I'm as opinionated as the next guy, so I couldn't resist replying. But not on his terms! What's the point in repeating an absurd exercise? The first thing that was obvious was that the list would be better if it were longer, since one of the best things about lists is how they can stimulate awareness of more than "the usual suspects." Tommasini's list is, I suppose, fine as a starting point for neophytes, but it's more useful, and more fun, to explore some roads less traveled.

I didn't have a preconceived idea of how long it should be. Rather, I went through my collection and eliminated every composer I didn’t think would remotely qualify as "great," then got to work. And it's not as though there weren't hard choices made in putting my list together. Even getting the list down to the 213 people included in my first draft left off some favorites, and after whittling it to 150 choices, the process became agonizing. I settled on 111 because that was the point I was at when I realized that there would be no getting it down to the next nice round number (and because it made for a nice Spinal Tap paraphrased reference.)

Of course, my list reflects my tastes. So yeah, Berlioz is missing. I think he's overrated. But leaving him off this list doesn't mean I think his music has no value – just not as much value as that by the people who are on the list. Only one of the people on Tommasini's list didn't make mine – Verdi – and I am far from sanguine about that. I admit that it is an indefensible choice from any perspective except personal taste; I just don't care about opera as much as Tommasini does, Verdi, though an innovator within the realm of opera, unlike Wagner had negligible compositional impact outside opera, and Verdi's non-operatic work is relatively inconsequential (I count his Requiem as operatic).

Unlike Tommasini, I'm looking at the whole history of "classical" music. Deliberately not including living composers because we haven't had enough time to consider their merits makes no sense. Every person in his or her lifetime gets to consider all but the youngest composers for the same amount of time as s/he can devote to evaluating dead composers. (There is also the silly situation of having automatically eliminated Elliott Carter, born in 1908, while having seriously considered Dmitri Shostakovich, born in 1906, and Benjamin Britten, born in 1913 – both mentioned by Tommasini, though they didn't make his final cut. And when Tommasini wrote his article, Milton Babbitt wasn’t eligible, but now, a week later, Babbitt sadly qualifies.) Is it a little riskier? Perhaps history's judgment will differ. So what? Show some balls. Anyway, we are alive now, and will use the list now, not in 200 years, so I include 15 living composers.

Tommasini also eliminated from consideration all composers before J.S. Bach, finding them too alien (his specific – and I think misguided – words were, "The traditions and styles were so different back then as to have been almost another art form"). I think that should be beside the point. It may be somewhat true relatively speaking, but far too much is lost if six centuries of music are summarily dismissed (I find 21 composers born before 1685 to be worthy of inclusion). What is the point of making a list such as this if one is not comprehensive of eras? His is an outdated attitude; when he was growing up, early music was considered exotic and was rarely performed, but great strides have been made in the decades since. It is significant, I think, that the first composer on my list, Hildegard von Bingen, has become quite popular outside of the early music -- or even classical -- cognoscenti over the past two decades.

Which brings me to another difference between my list and his: I'm not ranking the composers, but instead listing them in chronological order. However, the importance I assign to specific composers can be deduced from how many recording recommendations I make. Anyone with more than one is a major figure; more than two, among the elite. (Don't bother trying to read any significance into who gets his face next to his entry and who doesn't, though, as that's mostly based on availability and layout design.)

What ultimately makes my list better than his, in the most general sense, is that aside from Bach, Tommasini covers less than two centuries. (Mozart was born in 1756; Bartok died in 1945). Even including Bach, his list spans a mere 250 years. Mine spans ten centuries. Granted, that's easier when the list is eleven times longer, but length of the list is part of the problem in the first place. Tommasini's list is mostly useful for learning about Tommasini. I hope mine helps people to learn about classical music. That's why I've included recommended recordings. I'm not necessarily saying these are the best recordings of these pieces, by the way. Sometimes I've chosen recordings primarily because their program is the best overall introduction to the composer (though all of the performances are excellent). If my favorite isn’t on iTunes but another excellent version is, I generally went with the more easily accessible one. (And I mostly avoided albums with music by more than the chosen composer it's recommended for.)

And since my list is so long, this is part one of two. Hey, Tommasini took two articles to justify his tiny little list; my list’s eleven times longer.

Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179)

The inclusion of Hildegard (pictured above) on this list is not political correctness. First, she is historically important as one of the earliest non-anonymous composers to leave a significant body of work. Second, her work has artistic value due to the great imagination she showed in word-setting and the unfettered melodicism and expressive melismatic writing of her monadic (a single line of music, with no harmonies or counterpoint) songs, so much freer than the chant styles it evolved from.

Voice of the Blood: Sequentia/Joachim Kühn (Deutsche Harmonia Mundi)

Pérotin AKA Perotinus (c.1160-1225)

Pérotin’s predecessor at Notre Dame, Léonin, was the first named composer from whom we have polyphonic music. It was Léonin's polyphonic (and rhythmic, and perhaps notational) innovation in superimposing a faster-moving melody on a chant (organum) that Pérotin built upon when he expanded his music to three and four voices: his Viderunt omnes and Sederunt principles are the earliest written examples of four-part music in Europe. Pérotin’s music and the Notre Dame style in general were hugely influential; even now, Minimalist composer Steve Reich cites Pérotin’s method.

Viderunt omnes; Alleluia posui adiutorium; Dum sigillum summi Patris; Alleluia nativitas; Beata viscera; Sederunt principes: Hilliard Ensemble/Paul Hillier (ECM)

Guillaume de Machaut (c.1300-1377)

Machaut created masterpieces of both liturgical and secular musics (and I picked the recommended recording partly to reflect that), and was a vastly influential figure both musically (the epitome of the Ars Nova) and poetically. His Notre Dame Mass is the first known mass from the pen of a single non-anonymous composer. His extensive works (including around 400 poems, many being song lyrics) contributed to the codification of musical and poetic forms, especially song types.

Notre Dame Mass; “The Lay of the Fountain”; “My end is my beginning”: Hilliard Ensemble/Paul Hillier (Hyperion)

Guillaume Dufay (c.1400-1474)

Dufay was the most famous composer of his time, and at the center of the dominant Burgundian style. He was a bridge from the isorhythmic practices of the late Medieval period and the harmonic and melodic practices of the early Renaissance.

Missa Se la Face Ay Pale: Diabolus in Musica/Antoine Guerber (Alpha)

Johannes Ockeghem (c.1410-1497)

Ockeghem’s contrapuntal mastery led to him being considered Dufay’s successor as greatest living composer; his Missa Prolationum consists entirely of mensuration canons. His is the earliest surviving polyphonic Requiem.

Requiem, Missa Mi-Mi, Missa Prolationum: Hilliard Ensemble/Paul Hillier (Virgin Veritas) Josquin des Prez (c.1440-1521)

Josquin des Prez (c.1440-1521)

The epitome of the Franco-Flemish school, Josquin was Ockeghem's successor as "the greatest," widely admired for his technical mastery. He was equally likely to write austerely or ornately, and equally adept at either. His influence was amplified by the more widespread promulgation of his works afforded by the invention of music printing (though there was also a brisk trade in misattributed works assigned, after his death, to his name for commercial reasons). His Missa Pange Lingua, perhaps his last work, is a masterpiece of the paraphrase technique and uses a hymn by Thomas Aquinas.

Missa Pange Lingua; Missa La Sol Fa Re Mi; motets: Tallis Scholars/Peter Phillips (Gimell)

Pierre de La Rue (c.1460-1518)

In a way, La Rue was the inspiration for this list; while listening to his Requiem, I thought, "Any great composers list that doesn’t include this man doesn’t work for me." Another one of the great Franco-Flemish polyphonists (strongly influenced by Josquin), his trademarks are dense textures, extreme chromaticism, and favoring lower ranges; his Requiem is an extreme example of the latter.

Missa pro defunctis (Requiem); Missa de Beata Virgine: Ensemble Officium/Wilfried Rombach (Christophorus) Thomas Tallis (c.1505-1585)

Thomas Tallis (c.1505-1585)

Tallis is such an iconic English composer that he even has a feast day in the Episcopalian church. But he had to be stylistically versatile, as the changing rulers of England jerked the country's religion back and forth between Roman Catholicism and Anglican Protestantism (from which the Episcopalians split off). This also meant that he moved back and forth between Latin and English texts; being in at the beginning of the Anglican rite and composer of some of the first sacred music using English texts amplified his iconic status. He even showed up as a character in the Showtime historical soap opera The Tudors, played by Joe Van Moyland.

Complete Works, vol. 2: Music at the Reformation: Mass for Four Voices; Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis; Sancte Deus; Conditor Kyrie; Remember not, O Lord God; Hear the voice and prayer; If ye love me; A new commandment; Benedictus; Te Deum for meanes: Chapelle du Roi/Alistair Dixon (Signum, CD) Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (c.1525-1594)

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (c.1525-1594)

Palestrina was the first great Italian-born composer; raised on Franco-Flemish polyphony, he streamlined it somewhat (helping to make texts more intelligible) and de-emphasized dissonance. A prolific composer, he wrote over a hundred masses; the recommended album can be bought as a separate CD (the same program as appears on iTunes) but can also be found in a great five-CD bargain set issued by the budget label Brilliant Classics, which will give you a big dose of the prototypical Italian Renaissance composer.

Missa Papae Marcelli; Stabat Mater; Missa L'homme Armé for 5 voices: Pro Cantione Antiqua/Bruno Turner & Mark Brown (Alto)

Orlando di Lasso [AKA Roland de Lassus] (1532-1594)

Lassus was the ultimate flowering of the Franco-Flemish polyphonic style. Much in demand, and so respected that he was even knighted, he was very musically conservative in his mass settings, yet wildly innovative in some other forms, and prolific in using many forms and languages.

Psalmi Davidis Poenitentiales [Penitential Psalms]: Collegium Vocale Gent/Philippe Herreweghe (Harmonia Mundi)

William Byrd (ca.1540-1623)

Unlike Tallis, with whom he published a book of 34 motets after Queen Elizabeth I had granted them the sole permission for printing music and ruled music paper in England, Byrd was barely closeted Catholic; his Latin masses were composed for furtive celebrations of the Catholic Mass. (He wrote for Anglican services as well, and shares an Episcopalian feast day with Tallis.) His secular instrumental compositions, especially for keyboard, also constitute a formidable legacy.

Mass for 5 Voices; Mass for 4 Voices; Mass for 3 Voices: Pro Arte Singers/Paul Hillier (Harmonia Mundi)

The Complete Keyboard Music: Davitt Moroney (Hyperion)

Giovanni Gabrieli (c.1553/56-1612)

After studying with Lassus, Gabrieli became an innovator in spatially oriented music, and a major bridge from Renaissance to Baroque. He and his uncle Andrea famously composed vocal and instrumental music for the space of St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice, which had a pair of organs at opposite sides as well as multiple lofts for choirs and brass players; they took advantage of this with music written for two, three, or four groups answering/echoing each other, and with carefully specified dynamics (something that had not been previously notated).

The Glory of Gabrieli: Gregg Smith Singers/E. Power Biggs/Edward Tarr Brass Ensemble/Gabrieli Consort La Fenice/Texas Boys Choir (Sony Classical)

Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562-1621)

"The Orpheus of Amsterdam" came from a family rich in organists, but he was the greatest of all. He may have started as early as age 15 in the organ post he held for rest of his life. His fame brought many pupils, and his influence on several generations of German organists (including J.S. Bach) was vast, particularly his conception of the organ fugue.

Keyboard Music: Fantasia Chromatica; Onder een linde groen; etc.: Christopher Herrick (Hyperion)

John Dowland (1563-1626)

One of the greatest songwriters ever, in any genre, this English composer is especially loved for his melancholy songs. Of all the composers listed so far, he had the style most easily accessible to fans steeped in pop music (singer accompanying himself on lute is plainly analogous to folksinger/guitarist), and both Elvis Costello and Sting have recorded Dowland songs.

Flow My Tears and Other Lute Songs: Steven Rickards/Dorothy Linell (Naxos)

Carlo Gesualdo (c.1566-1613)

Even now that we have acclimated to much more dissonance, Gesualdo's avant-garde harmonies remain both piquant and surprising. He was famous in his time for his madrigals, which contain his most extremely innovative harmonies, but employed a madrigal style (deeply musically expressive of the text) even in sacred music, of which his Tenebrae Responsories are a good example. He also had a distinct taste for texts of torturous emotionality, which some have linked to guilt over his murder of his first wife and her lover when he caught them in the act.

Fifth Book of Madrigals (1611): La Venexiana/Claudio Cavina (Glossa)

Tenebrae Responsories: Feria V - In Coena Domini, Feria VI - In Parasceve, Sabbato Sancto; Benedictus; Miserere: Hilliard Ensemble/Paul Hillier (ECM) Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643)

Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643)

The final link from Renaissance to Baroque, Monteverdi changed opera (which was new at the time) from dry and text-focused to musically thrilling, and his Orfeo, the Greek mythic of the bard Orpheus in the Underworld, is the earliest opera to be in the current repertory. He was equally the master of madrigals and of liturgical choral music, and of Renaissance polyphony and Baroque basso continuo, the latter of which he did much to promulgate; the modern conception of tonality and harmony first flowered in Monteverdi’s Fifth Book of Madrigals.

L'Orfeo: Anthony Rolfe Johnson/Julianna Baird/Lynne Dawson/Anne Sofie von Otter/Nancy Argenta/Mary Nichols/John Tomlinson/Diana Montague/Willard White/Monteverdi Choir/English Baroque Soloists/His Majesties Sagbutts & Cornetts/John Eliot Gardiner (Archiv)

Vespers of the Blessed Virgin: Montserrat Figueras/Maria Cristina Kiehr/Livio Picotti/Paolo Costa/Daniele Carnovich/Roberto Abbondanza/Pietro Spagnoli/Gerd Türk/Gian Paolo Fagotto/Guy de Mey/La Capella Reial/Coro del Centro di Musica Antica di Padova/Jordi Savall (Alia Vox)

Madrigals of War and Love (Book 8): Concerto Vocale/René Jacobs (Harmonia Mundi)

Archangelo Corelli (1653-1713)

With easy melodicism of his style and the supportive accompaniment of solo instruments, Corelli made the concerto matter and was a huge influence on all following Baroque concerto composers (Bach even arranged some of Corelli's concertos for keyboard). Corelli also started a line of Italian violin pedagogy that extends to the present day.

12 Concerti Grossi, Op. 6: The English Concert/Trevor Pinnock (Archiv)

Henry Purcell (1658-1695)

Purcell was the culmination of the glorious English musical tradition; following his early death, it would be two centuries before its revival. Composer of the first great English opera, Dido and Aeneas, Purcell has been cited as an influence by Pete Townshend of The Who, and Klaus Nomi took his showpiece "The Cold Song" from Purcell's King Arthur.

Dido and Aeneas; music for The Gordian Knot Unty'd: Lisa Saffer/Lorraine Hunt Lieberson/Michael Dean/Paul Elliott/Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra/Choir of Clare College, Cambridge/Nicholas McGegan (Harmonia Mundi)

François Couperin (1668-1733)

Couperin filtered the influence of Corelli through a French sensibility. He was especially famed as a keyboardist, and his technical writings influenced many, including Bach. Though he was adept in many formats, it is as an exemplar of the great French keyboard tradition that he is most remembered.

Pieces for Two Harpsichords: William Christie & Christophe Rousset (Harmonia Mundi) Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741)

Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741)

Another great in the history of the concerto, and for far more than just the four violin concertos famously bundled as The Four Seasons. Nonetheless, their fame is well deserved and is a fine example of his excellence in depictional music.

The Four Seasons; Violin Concertos RV 257, 376, 211: Giuliano Carmignola/Venice Baroque Orchestra/Andrea Marcon (Sony Classical)

Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764)

Rameau’s music is perhaps the most graceful and refined in the French keyboard tradition. He was also important in French opera, but his keyboard music communicates most easily with modern listeners.

Music for Hapsichord Vol. 2: Gilbert Rowland (Naxos) Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Here is my first agreement with Tommasini, not only for inclusion but in rank: this guy's #1. Master of every then-current genre except for opera (which he could have mastered as well, but nobody was asking (paying) him to); inventor of the keyboard concerto, and the supreme organist/harpsichordist of his time; idol of hundreds of composers to come, and often indirectly their teacher as well, as his acknowledged mastery led to his works being studied continuously after his death in a way and to an extent that surpassed all who came before him.

St. John Passion: Tessa Bonner/Emily van Evera/Caroline Trevor/Rogers Covey-Crump/David Thomas/Taverner Consort & Players/Andrew Parrott (Virgin Veritas)

Great Organ Works: Toccata & Fugue in D minor, BWV 565; Toccata & Fugue in F major, BWV 540; Toccata & Fugue in D minor "Dorian," BWV 538; Fantasia & Fugue in G minor, BWV 542; Fantasia in G major, BWV 572; Passacaglia in C minor, BWV 582; Prelude & Fugue in D major, BWV 532; Prelude & Fugue in E-flat major, BWV 552; Trio Sonata No. 3 in D minor, BWV 527; Canonic Variations on “Von Himmel hoch, da komm ich her,” BWV 769; Schübler Chorales, BWV 645-50: Helmut Walcha (Deutsche Grammophon)

Brandenburg Concertos; Orchestral Suites: English Concert/Trevor Pinnock (Archiv)

Complete Harpsichord Concertos: Trevor Pinnock/Kenneth Gilbert/English Concert (Archiv)

Goldberg Variations: Murray Perahia (Sony Classical)

George Frideric Handel (1685-1759)

Handel excelled at everything a composer could do in his time -- unlike Bach, he was a prolific composer of opera. Though not as devoted to fugues as Bach, he was better at selling himself, long maintaining his popularity in England through shifting musical fashions: after Italian opera faded in public esteem, he switched to English oratorio and became even better-loved.

Concerti Grossi, Op. 3; Water Music; Music for the Royal Fireworks: Linde Consort/Cappella Coloniensis/Hans-Martin Linde (Virgin Veritas)

Israel in Egypt: Nancy Argenta/Emily van Evera/Timothy Wilson/Anthony Rolfe Johnson/David Thomas/Jeremy White/Taverner Choir & Players/Andrew Parrott (EMI Classics)

Messiah: Heather Harper/Helen Watts/John Wakefield/John Shirley-Quirk/London Symphony Orchestra/Sir Colin Davis (Philips)

Domenico Scarlatti (1685-1757)

He earns inclusion on the strength of one of the most extensive bodies of work in a single form – keyboard sonatas (555 of them!) – in the history of music. His style was influential on the shift from the Baroque to the Classical era.

Harpsichord Sonatas, K 44, 52-3, 120, 124, 140-1, 144, 147, 426-7, 450, 461, 469, 531: Christophe Rousset (L'Oiseau-Lyre)

Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714-1787)

Gluck is the first composer to earn his way onto this list solely through his operas. It’s not just that they were great, it’s that they changed the history of opera. He stripped away the many superfluities of opera seria to make a more natural, more dramatically effective style.

Orfeo ed Euridice: Anne Sofie von Otter/Barbara Hendricks/Brigitte Fournier/English Baroque Soloists/John Eliot Gardiner (EMI Classics)

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1714-1788)

So much more than just J.S. Bach's son: a major figure in the formation of the Classical style, a keyboard virtuoso who pioneered a hyper-expressive playing style and whose theoretical writings created the foundation of modern piano technique.

Keyboard Concertos (Complete), Vol. 14: Concertos in A minor, Wq26; E-flat major, Wq40; Sonatina for Keyboard & Orchestra in C major, Wq 101: Miklós Spányi/Opus X/Petri Tapio Mattson (Bis)

Franz Josef Haydn (1732-1809)

The man who made symphonies interesting. The form had only recently evolved, yet in Austria largely repeated a small group of clichés; Haydn expanded their breadth and varied their format. His great wit and imaginative innovation made the new form far more interesting. He was, if anything, even more crucial in the development of the string quartet.

Symphonies Nos. 93-104 "London": London Philharmonic Orchestra/Eugen Jochum (Deutsche Grammophon)

The Haydn Project: String Quartets, Op. 20 No. 5; Op. 33 No. 2 "Joke"; Op. 54 No. 1; Op. 64 No. 5 "Lark"; Op. 74 No. 3 "Rider"; Op. 76 No. 2 "Quinten"; Op. 77 No. 1 "Lobkowitz"; Emerson String Quartet (Deutsche Grammophon) Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

The second-earliest composer on Tommasini's list, and so graceful in his compositional mastery that his music seems both easier than it really is and utterly timeless. Here's a longer take on his brilliance.

Symphonies Nos. 36, 38-41: Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields/Sir Neville Marriner (Philips)

The Piano Concertos & Rondos K.382 & 386: Murray Perahia/English Chamber Orchestra (Sony Classical)

Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute): Nicolai Gedda/Gundula Janowitz/Walter Berry/Lucia Popp/Gerhard Unger/Gottlob Frick/Ruth-Margaret Pütz/Elisabeth Schwarzkopf/Christa Ludwig/Marga Höffgen/Franz Crass/Philharmonia Chorus & Orchestra/Otto Klemperer (EMI Classics)

Don Giovanni: Cesare Siepi/Anton Dermota/Deszo Ernster/Elisabeth Grümmer/Elisabeth Schwarzkopf/Erna Berger/Walter Berry/Vienna State Opera Chorus/Vienna Philharmonic/Wilhelm Furtwängler (EMI Classics)

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Beethoven's #2 on Tommasini’s list, a game-changer who made music about personal expression to a far greater degree than anyone before him. (On his birthday last year, I wrote about various recordings of his symphonies.)

Symphonies Nos. 1-9: Cheryl Studer/Delores Ziegler/Peter Seiffert/James Morris/Westminster Choir/Philadelphia Orchestra/Riccardo Muti (EMI Classics)

Piano Concertos Nos. 1-5; Choral Fantasia for Piano, Chorus and Orchestra: Melvyn Tan/Nancy Argenta/Evelyn Tubb/Mary Nichols/Caroline Trevor/Rufus Müller/Howard Milner/Richard Wistreich/Schütz Choir of London/London Classical Players/Roger Norrington (EMI Classics)

Late String Quartets: Alban Berg Quartet (EMI Classics)

Piano Sonatas Nos. 1-32; Andante favori in F major: Alfred Brendel (Philips)

Carl Maria von Weber (1786-1826)

The man who moved opera into the Romantic era, and proved massively influential in the process. His death at age 39 deprived music of a genius practitioner, but he had already established himself as an icon of the German operatic tradition; as a national tradition, rather than German-born composers writing in Italian style, it could be said to start with Weber.

Der Freischütz: Theo Adam/Edith Mathis/Gundula Janowitz/Peter Schreier/Staatskapelle Dresden/Carlos Kleiber (Deutsche Grammophon)

Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868)

Arguably the greatest Italian composer of opera, and a master of both comic opera and dramatic opera. The choices below are respectively his best in each field. His knack for "hooks" has made excerpts from his operas popular with millions of people who never set foot in an opera house.

Il Barbiere Di Siviglia (The Barber of Seville): Cecilia Bartoli/Coro del Teatro Comunale di Bologna/Giuseppe Patanè/Leo Nucci/Orchestra del Teatro Comunale di Bologna (Decca)

William Tell: Luciano Pavarotti/Mirella Freni/Nicolai Ghiaurov/Sherrill Milnes/National Philharmonic Orchestra of London/Riccardo Chailly (Decca)

Franz Berwald (1796-1868)

The first "underrated" on my list, a Swedish symphonist of great originality. Unable to support himself by music in his home country, where his harmonic and structural innovations were looked at askance (he was more respected in Germany and Austria), for most of his life he had to compose in his spare time. His spurt of four mature symphonies in three years is particularly impressive under these circumstances.

Symphonies Nos. 1-4; Symphony in A major; Estrella de Soria Overture; The Queen of Golconda Overture: Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra/Roy Goodman (Hyperion) Franz Schubert (1797-1828)

Franz Schubert (1797-1828)

The master of melody is #4 on Tommasini's list. Though Schubert was not a particularly well-known composer in his day, his star has been rising ever since. In the fictional story of Mozart's life, Antonio Salieri was the jealous villain; in the real story of Schubert's life, Salieri was the generous hero, granting him a scholarship at the Imperial seminary school and giving gratis tutoring to the impoverished Schubert, exposing him to the music of Mozart, and letting Schubert lead the school orchestra in original compositions. In his early efforts Schubert was a Classical composer in brief forms, but later on expanded his structural ambitions (Schumann famously lauded the "Great" Symphony’s "heavenly length") and became a full-blown Romantic.

Symphonies Nos. 1-6, 8-9: Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra/Karl Böhm (Deutsche Grammophon)

Piano Sonatas D.958, 959, 960: Murray Perahia (Sony Classical)

Winterreise: Hans Hotter/Gerald Moore (EMI Classics)

Piano Quintet in A major "The Trout"; Arpeggione Sonata: Emanuel Ax/Guarneri Quartet members/Julius Levine; James Levine/Lynn Harrell (RCA Red Seal)

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809-1847)

Despite being even more talented as a child prodigy than Mozart, and despite a huge number of excellent compositions, Mendelssohn somehow doesn' seem to get much respect -- yet audiences love his music. Of the post-Beethoven generation, he was the composer who managed to channel that influence into the least Beethovenesque music. My Mendelssohn guide is here.

Symphonies Nos. 1-5; Overture "The Hebrides" (Fingal's Cave); Overture to A Midsummer Night's Dream; Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage; Ruy Blas; Overture for Wind Instruments; Trumpet Overture; Overture "The Fair Melusina"; Scherzo from the Octet: London Symphony Orchestra/Claudio Abbado (Deutsche Grammophon)

Octet; String Quintets Nos. 1 & 2; String Quartet No. 2: Hausmusik London (Virgin Veritas)

Songs Without Words: Daniel Barenboim (Deutsche Grammophon) Frederic Chopin (1810-1849)

Frederic Chopin (1810-1849)

The first great Polish composer more or less only wrote for piano. A child prodigy, at age eight he played a public concert and had already begun composing short pieces. He was first published at 15, and by 20 had been hailed as "a genius" by Schumann. He combined spectacular technique with poetic sensibilities and was harmonically advanced for his time, favoring daring modulations. He created a new stylistic vocabulary for the piano, utterly wedded to the instrument's strengths and eschewing pseudo-orchestral effects. So though as a composer he basically only had one focus, he did it so well, and so imaginatively, and so influentially, as to become practically the patron saint of pianists.

The Original Jacket Collection: Rubinstein Plays Chopin: Nocturnes; Mazurkas; Ballades; Scherzos; Polonaises; Sonatas; Waltzes; Preludes; New Etudes; etc.: Arthur Rubinstein (RCA Red Seal)

Robert Schumann (1810-1856)

Despite severe mental illness, Schumann managed to leave important bodies of symphonic and pianistic work while becoming the epitome of the tortured Romantic artist. His solo piano work best exemplifies his mercurial personality.

Carnaval; Papillons; Kinderszenen (Scenes from Childhood); Arabeske: Nelson Freire (Decca)

Franz Liszt (1811-1886)

Also very important to the history of piano playing, albeit not as sublime as Chopin. Much of his output consisted of gaudy showpieces, but some had their merits, and his Sonata is an altogether more serious and structurally influential matter.

Piano Concertos Nos. 1 & 2; Piano Sonata in B minor: Sviatoslav Richter/London Symphony Orchestra/Kirill Kondrashin (Philips)

Richard Wagner (1813-1883)

Also on Tommasini's list. Yet another man who changed opera; few have devoted themselves to it so thoroughly, both in the writing of and the writing about. There was grand opera before Wagner, but he took grandness to an entirely new level of length and bombast, along the way (with Tristan und Isolde) sparking succeeding generations' harmonic adventures.

Der Ring des Nibelungen: George London/Gustav Neidlinger/Kirsten Flagstad/Set Svanholm/Birgit Nilsson/Hans Hotter/James King/Régine Crespin/Wolfgang Windgasse/Vienna Philharmonic/Georg Solti (Decca), in its four parts:

Das Rheingold

Die Walküre

Siegfried

Götterdämmerung

Tristan und Isolde: Ludwig Suthaus/Kirsten Flagstad/Blanche Thebom/Josef Greindl/Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau/Rudolf Schock/Edgar Evans/Rhoderick Davies/Chorus of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden/Philharmonia Orchestra/Wilhelm Furtwängler (EMI Classics)

César Franck (1822-1890)

The greatest Belgian composer since the Renaissance has one of the smallest bodies of work of anyone on this list, and only seven compositions regularly heard in concert -- and that’s using a liberal definition of "regularly" (though in addition, organists highly esteem his works for their instrument). Nonetheless, his ideas of cyclical structure became hugely influential on following generations of French composers (he spent the last 17 years of his life teaching at the Paris Conservatoire), and if he had only composed his mighty Symphony in D minor -- the embodiment of those ideas -- he might still be on this list.

Symphony in D minor; Symphonic Variations; “Le Chasseur Maudit”: Boston Symphony Orchestra/Charles Munch; Leonard Pennario/Boston Pops/Arthur Fiedler (RCA Red Seal)

Anton Bruckner (1824-1896)

In a way, the Wagner of the symphony (and he was certainly as influenced by the operatic maestro as much as any symphonist ever was), expanding its length and its structure. His career was a constant struggle against naysayers, but history has vindicated him. Unsure of himself and something of a country bumpkin (or a holy fool) amidst the Byzantine tangle of intrigue and factionalism that was 19th century Vienna, he revised his symphonies numerous times, and let some of his pupils get in their whacks as well, leading to a welter of confusion regarding multiple editions. Yet somehow, all except some first versions of some of the early symphonies (everything from the Fifth on is safe) generally make an impressive impact regardless.

Symphonies Nos. 1-9: Staatskapelle Dresden/Eugen Jochum (EMI Classics)

(If you're buying CDs, not MP3s, and want the best combination of sound and performance, or if you want a set that includes the unpublished -- until after Bruckner's death -- symphonies called No. 0 "Die Nullte" and Study Symphony in F, go for Stanislaw Skrowaczewski’s 12-CD set on Oehms. It's also available on iTunes in 11 separate downloads. Skrowaczewski’s tempi are also less interventionist than Jochum’s.)

Masses Nos. 1-3: Edith Mathis/Maria Stader/Claudia Hellmann/Marga Schiml/Ernst Haefliger/Wieslaw Ochman/Kim Borg/Karl Ridderbusch/Choir & Symphony Orchestra of Bavarian Radio/Eugen Jochum (Deutsche Grammophon) Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Another on Tommasini's list. No label (of style or format) put on Brahms can adequately encapsulate his many-faceted mastery. He combined Classical and Romantic (not to mention Baroque and Renaissance influences) into a Janus-like style of richness and density that Wagnerians considered reactionary and obsolete, yet Schoenberg later declared revolutionary. Brahms is considered an intellectual composer, but -- particularly in his piano music – often taps deep channels of emotion.

Symphonies Nos. 1-4: North German Radio Symphony Orchestra/Günter Wand (RCA Red Seal)

Concerto for Violin; Sonatas for Violin & Piano, Nos. 1-3: Aaron Rosand/Monte Carlo Orchestra/Hugh Sung (Vox Classics)

Variations and Fugue on a theme by Handel; Rhapsodies, Op. 79; Piano Pieces, Opp. 118-19: Murray Perahia (Sony Classical)

German Requiem: Elisabeth Schwarzkopf/Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau/Philharmonia Chorus & Orchestra/Otto Klemperer (EMI Classics)

Camille Saint Saëns (1835-1921)

A child prodigy who also had a lengthy career, Saint Saëns is not respected as much as he should be; it's almost as if he made composing seem so easy that people think his is not worth respecting. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Piano Concertos Nos. 1-5; Allegro appassionato; Rapsodie d'Avergne; Wedding Cake: Caprice-Valse; "Africa" Fantasy: Stephen Hough/City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra/Sakari Oramo (Hyperion)

Georges Bizet (1838-1875)

Mostly known for opera (especially his immortal Carmen), Bizet also wrote a fine, if somewhat backward-looking (yet still fresh-sounding) symphony. Nonetheless, it's his theatrical music on which his reputation rightly stands.

Carmen: Angela Gheorghiu/Roberto Alagna/Inva Mula/Thomas Hampson/Elizabeth Vidal/Isabelle Cals/Ludovic Tézier/Nicolas Cavallier/Nicolas Rivenq/Yann Beuron/La Lauzeta, Children's Choir of Toulouse/Choir "Les Éléments"/National Orchestra of the Capitol of Toulouse/Michel Plasson (EMI Classics)

Modeste Mussorgsky (1839-1881)

Eccentric, alcoholic beyond even the standards of musicians, not very good at actually finishing things, almost making Franck look prolific in comparison, Mussorgsky makes this list by the skin of his teeth, on the strength of one epically great opera (below) and one good opera (Khovanshchina), one spectacular piano piece (Pictures at an Exhibition), and the finest Russian songs ever written (notably the short cycles Songs & Dances of Death and Sunless).

Boris Godunov: Nicolai Ghiaurov/Lucia Valentini Terrani/Mihayl Svetlev/Nicola Ghiuselev/Ruggero Raimondi/Philip Langridge/Orchestra & Chorus of La Scala/Claudio Abbado (Sony Classical)

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

An epitome of Romanticism, all the more poetic and warm – and often touching melancholic, not least in his "Pathétique" Symphony -- for being Russian.

Violin Concerto; Romeo & Juliet Fantasy-Overture after Shakespeare; Meditation for Violin and Orchestra: Dmitry Sitkovetsky/Academy of St. Martin in the Fields/Neville Marriner (Hänssler Classic)

Symphonies Nos. 4-6: Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra/Kurt Sanderling, Evgeny Mravinsky (Deutsche Grammophon)

Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904)

No less knowledgeable a composer than Brahms saw Dvořák's talent and shepherded the indigent young composer to fame and fortune. The Czech (specifically Bohemian and Moravian) flavors of his music make it immediately distinctive.

Symphonies Nos. 7-9; Carnival Overture: Cleveland Orchestra/George Szell (Sony Classical Masterworks Heritage)

Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924)

The delicate, inimitably French charms of Fauré's music have proven timeless. There's a large amount of it that remains unheard by the average collector, but there's no denying the powerful draw of the three masterpieces on my recommended recording, and the Requiem in particular is an undeniable and quite distinctive masterpiece.

Requiem; Pavane; Pelléas et Mélisande: Elly Ameling/Bernard Kruysen/Jill Gomez/Netherlands Radio Chorus/Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra/Jean Fournet, David Zinman (Philips)

Leoš Janáček (1854-1928)

One of the three greatest Czech composers, Janáček started out as a Dvořák acolyte but matured into a highly individualistic stylist of unusual imagination.

Glagolitic Mass; The Diary of One Who Disappeared: Evelyn Lear/Hilde Rössl-Majdan/Ernst Haefliger/Franz Crass/Kay Griffel/Women's Choir/Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra/Rafael Kubelik (Deutsche Grammophon)

The Makropulos Affair; Lachian Dances: Elisabeth Söderström/Peter Dvorsky/Anna Czaková/Dalibor Jedlicka/Václav Zitek/Ivana Mixová/Vladimir Krejcik/Vienna Philharmonic/Charles Mackerras (Deutsche Grammophon)

Giaccomo Puccini (1858-1924)

The last melodic genius of the great Italian opera tradition; his trademark work (below) is so iconic and universal in appeal that it has been updated and transformed even in modern pop modes.

La Bohème: Plácido Domingo/Monserrat Caballé/Sherrill Milnes/Judith Blegen/Ruggero Raimondi/Vincente Sardinero/Noel Mangin/John Alldis Choir/Wandsworth School Boys' Choir/London Philharmonic Orchestra/Georg Solti (RCA Victor Red Seal) Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

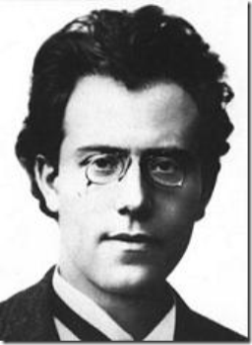

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Perhaps no omission from Tommasini's list excited more controversy than Mahler's. He made the symphony a form for post-modern expression with his ironic quotations, his rustic peasant dances, and his Freudian juxtapositions; he was also one of the greatest conductors in history and had a superlative command of orchestration. I wrote about him at length here.

Symphonies Nos. 1-9; 10:I: London Philharmonic Orchestra/Klaus Tennstedt (EMI Classics)

Das Lied von der Erde: Christa Ludwig/Fritz Wunderlich/Philharmonia Orchestra/Otto Klemperer (EMI Classics)

The second and final part of this list is here. For those who just can't wait to know how it turns out, I'll reveal now that #111 will be David Lang. - Steve Holtje