If there is a thread that unites the varied bodies of work that the protean painter Brenda Goodman has produced over her five-decade career, it is the sense of urgency -- in the need of the artist to articulate her thoughts and emotions onto the painted surface, but also a feeling of immediacy in the directness of expression, the painterly "hand" manifest in the work. Even in the Ingre-esque drawings of her work in the 1970s, one senses Goodman's need to capture a moment, a relationship between her psychological characters, and then move on, leaving a generous space unfinished for the viewer to move around in. This restlessness pervades her work, in fact defines it, as she jumps from style to style, figure to abstraction, throughout different periods.

What is most surprising about Goodman's recent work, now on view at David & Schweitzer, is a feeling of quiet introspection, a Proustian sense of contemplation, that pervades the paintings and works on paper, all created in the past year. To anyone familiar with Goodman's work, it comes as no surprise that to unfold the imagery, a hybrid of painterly syntax, might require some thoughtful participation. These powerful, compact paintings reveal themselves slowly, with the contingency of her previous works replaced by a weightier, architectural feel, at once both formally strong and psychologically layered with meaning.

An aspect of the Surrealist movement, which holds greater relevance to many painters working today, was that there were two quite different approaches, stylistically and philosophically, to painting. The first, most iconic, was the "dream illustration" typified by Dalí; the second was a more literary-based "automatic writing" developed by Masson. It was this second, inward-looking manner of working that would have the greatest impact on American artists like Motherwell and Pollock. Goodman's paintings harken back to both ways of working.

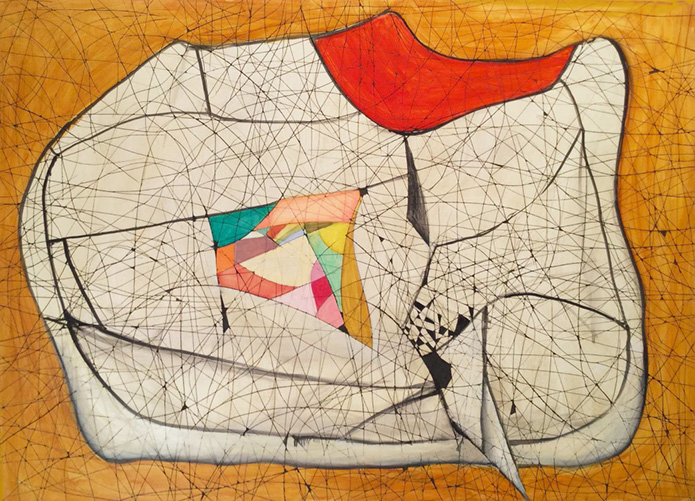

Most of these works begin with a scarified surface, for example Lickety Split (2017) (above), whose underlying mark-making resembles a Mark Tobey or a Masson. It is from this unconscious, random scraffiti she "discovers" forms; but through a process of editing and layering, these forms coalesce and resolve into "head" shapes that in turn form a sort of proscenium or stage, which frames an imagined, internal subconscious scene. The connection to the Abstract Expressionists is manifest in Goodman’s process; as she says, "I would say Lickety Split is probably one of the riskiest paintings I’ve ever done because it was a beginning, that upon looking at it for a few days, quickly became an end, and it was done." This ambiguity, in which we are both "seeing" and "seeing into," along with the painter, gives these paintings an internal tension as we unpack the imagery like a matryoshka doll. Goodman embraces wholeheartedly these contradictions; seldom is ambiguity been depicted so clearly.

Goodman's anthropomorphized "stage heads" suggest the trope that Picasso used in his Guéridons of the 1920s. Goodman's work in the '70s used the idea of the painting as stage to give space to her morphing characters in scenes, imaginary relationships, and stories. Here, Goodman reinvests the concept further with personal anecdote, drawing on memories of her mother, childhood stories, and references to her partner Linda. In Tomorrow's Promise (2017) (top), stage, character, and story conflate. We can almost feel Goodman remembering and reflecting and recording memories through the medium of paint. Godard wrote that the most beautiful and difficult thing in cinema was capturing on film the moment when someone changes their mind. With these new paintings Goodman seems to be on the same search, for an elusive perfect moment, a memory from the past, happening still.